Life Extension Benefits of Methionine Restriction

by Ben Best

CONTENTS: LINKS TO SECTIONS BY TOPIC

- METHIONINE BASICS

- METHIONINE RESTRICTION EFFECTS

- METHIONINE RESTRICTION FOOD DATA

- METHIONINE RESTRICTION DIET

![[HEART MUSCLE METHIONINE]](http://www.supremepundit.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/meth_heart-1.jpg) |

I. METHIONINE BASICS

Methionine is the only essential amino acid containing sulfur. Methionine is the precursor of the other sulfur-containing amino acids: cysteine, taurine, homocysteine, and cystathione. Methionine is essential for the synthesis of proteins and many other biomoleules required for survival. Rats fed a diet without methionine develop fatty liver disease which can be corrected by methionine supplements [DIGESTIVE DISEASES AND SCIENCES; Oz,HS; 53(3):767-776 (2008)]. Dietary methionine is essential for DNA methylation. Reduced DNA methylation results in genetic instability, aberrant gene expression, and increased cancer.

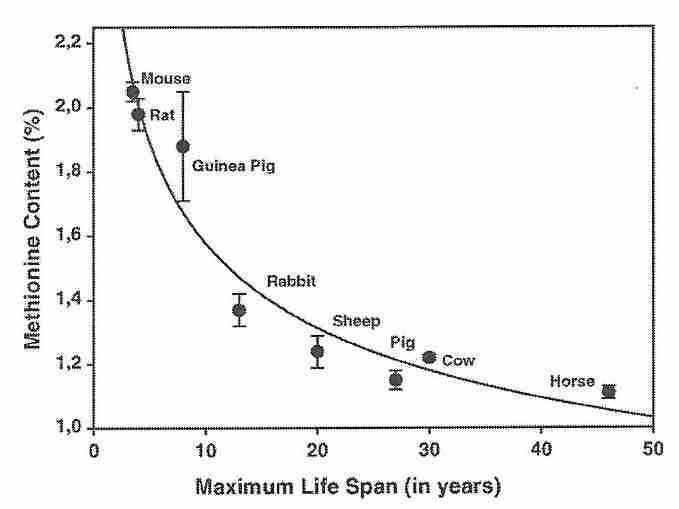

The above paragraph is the first paragraph from the section on methionine in my article dealing with the Methionine Cycle. Material in that article is useful background for the information below. Note, however, that there is an inverse correlation between lifespan and the methionine content of protein in the heart muscle of eight mammalian species [MECHANISMS OF AGEING AND DEVELOPMENT; Ruiz,MC; 126(10):1106-1114 (2005)]. The sulfur-containing amino acids methionine and cysteine are the most readily oxidized of any of the amino acids — both as free amino acids or in proteins. Methionine is oxidized to methionine sulfoxide, but methionine sulfoxide reductases enzymatically regenerate methionine [BIOPHYSICA ET BIOCHEMICA ACTA; Lee,BC; 1790 (11): 1471-1477 (2009)].

II. METHIONINE RESTRICTION EFFECTS

Substantial evidence indicates that as much as half of the life-extension benefits of CRAN (Calorie Restriction with Adequate Nutrition) are due to restriction of the single amino acid methionine. In a study of rats given 20% the dietary methionine of control rats, mean lifespan increased 42% and maximum lifespan increased 44% [THE FASEB JOURNAL;Richie,JP; 8(15):1302-1307 (1994)]. Blood glutathione levels were 81% higher in the methionine-restricted rats at maturity, and 164% higher in old age. In other studies, methionine-restricted rats showed greater insulin sensitivity and reduced fat deposition [AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSIOLOGY; Hasek,BE; 299:R728-R739 (2010) and AGING CELL; Malloy,VL; 5(4):305-314 (2006)].

An experiment on mice given 35% the methionine of controls showed only a 7% increase in median life span [JOURNALS OF GERONTOLOGY; Sun,L; 64(7):711-722 (2009)]. Another mouse study showed lowered serum insulin, IGF−1, glucose, and thyroid hormone for methionine at one-third the normal intake. There was significant mouse mortality for methionine less than one-third normal intake, but with one-third intake of methionine maximum lifespan was significantly increased [AGING CELL; Miller,RA; 4(3):119-125 (2005)]. Rats generally show greater longevity benefits from CRAN than mice.

Mitochondrial free radical generation is believed by many biogerontologists to be a significant contributor to aging damage. Rats given 20% the dietary methionine of control rats show significantly decreased free radical generation from complex I and complex III of liver mitochondria as well as from complex I of heart mitochondria — associated with reduced oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA and protein [THE FASEB JOURNAL;Sanz,A; 20(8):1064-1073 (2006)]. These results are comparable to the reduced mitochondrial free radical generation seen in CRAN rats [ENDOCRINOLOGY; Gredilla,R; 146(9):3713-3717 (2005)]. Rats given 60% rather than 20% of the methionine of control rats showed nearly the same amount of reduced mitochondrial free radical generation and damage [BIOCHEMICA ET BIOPHYSICA ACTA; Lopez-Torres,M; 1780(11):1337-1347 (2008)]. Body weight was not reduced with 60% dietary methionine, leading to the conclusion that such reduction would not result in reduced growth in children [REJUVENATION RESEARCH; Caro,P; 12(6):421-434 (2009)]. It was concluded that methionine restriction is the sole reason for reduced mitochondrial free radical generation and damage associated with CRAN [Ibid.] and protein restriction [BIOGERONTOLOGY; Caro,P; 9(3):183-196 (2008)].

Evidence for the suggestion that methionine oxidation plays a significant role in lifespan can be found in the considerable lifespan extension benefits seen in transgenic fruit flies that overexpress a gene for repairing oxidized methionine in protein [PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES (USA); Ruan,H; 99(5):2748 (2002)]. The sulfur-containing amino acids methionine and cyteine are more easily oxidized in proteins than other amino acids [JOURNAL OF PHYSIOLOGY)], which is apparently related to the reduced free radical generation in mitochondria seen in methionine restriction. Both the fruit fly experiment and the methionine restriction experiments indicate a significant impact on lifespan from methionine oxidation.

It has been suggested that glycine supplementation has the same effect as methionine restriction. An experiment with glycine supplementation in rats showed a 30% extension in maximum lifespan [FASEB JOURNAL; Brind,J; 25:528.2 (2011)]. Additionally, three grams of glycine daily has been shown to improve sleep quality in young (average age 31) female Japanese adults [SLEEP AND BIOLOGICAL RHYTHM; Inagawa,K; 4:75-77 (2006)]

|

III. METHIONINE RESTRICTION FOOD DATA

The adjoining table (my Table 1) from [AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION; Young,VR; 59(suppl):1203s-1212s (1994)] indicates the essential amino acids most likely to be limited in plant protein foods. Cereal protein contains comparable sulfur-containing amino acids (including methionine) per gram as animal foods, whereas fruit and legume protein contain about 65% as much methionine. Nuts and seeds are particularly high in methionine, on average 20% higher in methionine than animal protein, although the absolute amount of protein in animal foods tends to be higher, which makes total methionine intake generally higher in animal foods. Vegetables are not shown in Table 1, but as described in Table 4 in the AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION paper from which Table 1 is taken, vegetables are on average in the 1-2% range for percent protein and fruits are in the 0.5-1% protein range — so neither fruits nor vegetables should be considered serious sources of protein (green peas are an exceptional vegetable with 5.4% protein, and avacado is an exceptional fruit with 2% protein). Cereals are typically 7-13% protein and legumes are typically 20-30% protein (soybeans are exceptionally high in protein even for legumes, being in the range of 35-45% protein).

The dry weight of beef, broccoli, peanuts, and peas is about one-third protein, whereas cereals and fruits are less than 10% dry weight protein. Unlike many other plant proteins, legumes are not particularly low in lysine, and they are close to animal protein in threonine content. Vegetarians attempting to achieve complete protein often combine cereals (which are relatively high in methionine for plant protein) with legumes (which are relatively high in lysine for plant protein).

![[PHYTIC ACID]](http://www.supremepundit.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/phytate-1.jpg) |

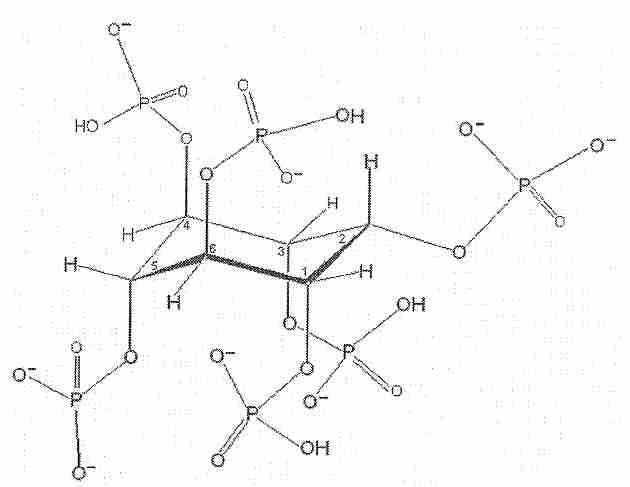

Lentils and other beans contain high amounts of phytic acid (phosphate-rich inositol), which can chelate positively-charged multivalent mineral ions (especially iron, zinc, magnesium, and calcium), preventing absorption. Soaking lentils and beans in warm water overnight not only makes them easier to cook, it allows some of the phytates to be soaked-out (and thrown-away with the water). Acidic solution (such as vinegar) better removes the phytates. Cooking also helps destroy phytates.

Although it would be very difficult to determine a diet providing optimum methionine for maximum human lifespan — even on the basis of rat experiments — evidence is convincing that reducing dietary methionine can help extend lifespan. The Table 2, listing milligrams of methionine per 100 grams of food (rather than per gram of protein, as in Table 1), could be helpful. Table values are based on [FOOD VALUES OF PORTIONS COMMONLY USED by Jean Pennington (1989)].

|

The absolute methionine content of a food is better evaluated knowing what the water, fat, carbohydrate, fiber, and protein content of that food is. A higher protein content and a lower methionine content is better than having a low methionine content because the food is low in protein and high in water, fat, or carbohydrate. Lima beans and rice are relatively high in both carbohydrate and methionine. Onions and strawberries are low in methionine, but are high in water and low in protein.

The data for Table 3 is taken from [NUTRITIVE VALUE OF FOODS; USDA Bulletin 72 (1981)], but is adjusted to give percent protein by dry weight. Percent water in the food is not related to the other columns. Fiber content is not given, and I suspect that fiber is equated with carbohydrate. I may have made a few errors, and I suspect that the data contains a few errors (garbage-in, garbage-out). But for the most part I think the data is good, my transcription is accurate, and my calculations are correct.

|

Brown rice would be more nutritious than white rice, except that the fats in germ that is removed to make white rice can go rancid. Ingestion of Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGES) is detrimental to health.

Table 4gives the percent fat obtained for selected items in the above table, and breaks down the fat into percent saturated, monosaturated, and polyunsaturated fat. Numbers are rounded to the nearest whole number, which is why the total percentages don’t always add to 100. Monosaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats are preferred to unsaturated fats except where there is rancidity. Again, ingestion of Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGES) is detrimental to health. I had no data for non-fat cheese, the only kind of cheese that I eat.

|

Table 5 gives relative proportions of all of the essential amino acids (plus tyrosine) for some representative high-protein animal foods as well as for some low-methionine plant foods.

Lysine is given after methionine because lysine is most often the limiting amino acid (the essential amino acid found in the smallest quantity relative to requirement) in cereals, nuts, and seeds — but lysine in abundant in legumes, for which methionine is typically the limiting amino acid [AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION; Young,VR; 59(suppl):1203s-1212s (1994)]. Lysine is therefore listed second in the table. Leucine is listed third because of its paradoxical ability to reduce fat in high doses [DIABETES; Zhang,Y; 56(6):1647-1654 (2007)] and low doses [DIABETES; Cheng,Y; 59(1):17-25 (2010)]. Leucine and threonine are the limiting amino acid in vegetables and fruits, although vegetables and fruits are too low in protein to be considered significant proteins sources. Trytophan restriction has been shown to have a modest (compared to methionine restriction) ability to extend lifespan in rats [ MECHANISMS OF AGEING AND DEVELOPMENT; Ooka,H; 43(1):79-98 (1988)], reputedly by opposing an age-related increase in brain serotonin.

Tyramine was evaluated because of claims that high dietary tyramine could have adverse reactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (I take deprenyl). But none of the foods listed have seriously high levels of tyramine, so tyramine is not really a concern.

Again, this data is taken from [FOOD VALUES OF PORTIONS COMMONLY USED by Jean Pennington (1989)]. I have adjusted the Pennington data to be standardized for 100 grams of food, rather than reproducing the variable quantities of food given, which makes comparison difficult. I may have made transcription errors, but probably not many (if any).

|

Confusion can be caused by the variable amounts of proteins in the foods. Some foods have high water content (such as onion), or high carbohydrate content (such as rice), or high fat content (such as nuts). To compare relative amounts of methionine in the proteins in the foods, I have created Table 6 in which I have adjusted the values to reflect milligrams of amino acid per gram of protein, rather than the per 100 grams of food used in the previous table. To do this, I first calculate dry weight [(100 − % water) / 100] and then divide by % protein. (Note that Persian/English walnuts contain 60% the protein of black walnuts, mostly because of higher fat content. This creates a misimpression that Persian/English walnuts are much lower in methionine than black walnuts.)

I make no guarantee that I have made no transcription errors in manually copying data from either table to my calculator.

>

|

I am searching for foods that are high in protein, but low in methionine, as a source of protein. Preferably the foods should be high in the essential amino acids (other than methionine), and low in fat (especially saturated fat) and low in carbohydrate. As sources of protein, the data in the Table 6 are important in proportion to the percent protein in the food, especially when the water content is low. As long as protein is adequate in the diet overall, other foods that are low in protein and high in water are not much of a concern from a methionine restriction point of view. Legumes offer the best tradeoff of low methionine, and high protein (high essential amino acids), particularly lentils and pinto beans. Adzuki beans would be a contender except that the high fiber content makes them hard to process. I prefer to get my fiber from other sources.

Table 7 was created by dividing methionine amount into the amounts of the other essential amino acids shown in Table 5. Thus, the numbers in the lysine column reflect how many times the lysine content of the food exceed the methionine content.

|

IV. METHIONINE RESTRICTION DIET

Pinto beans and lentils are the high-protein foods that show the best low-methionine, high-lysine profile, by a large margin. Lentils, however, are easier to soak before cooking to remove phytates, and produce a bit less odiferous flatulance than pinto beans. Both legumes, however, are high in phytic acid and raffinose oligosaccharides. Humans lack the enzyme to digest raffinose, which passes to the lower intestine where bacteria possessing the digestive enzyme create gases which can be quite odiferous.

Soaking pinto beans for 16 hours at room temperature only reduces raffinose oligosaccharides by 10%, and 90 minutes of cooling only cuts the raffinose oligosaccharide content in half [JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD CHEMISTRY; Song,D; 54(4):1296-1301 (2006)].

Just as the objective of calorie restriction is not to live without calories, methionine is an essential amino acid that can be reduced to 60% normal consumption to obtain most of the benefit [BIOGERONTOLOGY; Caro,P; 9(3):183-196 (2008)]. That dietary objective can be met without the need to consume legumes.