The virus you likely never heard of is steadily marching north from Brazil. It’s Zika, spread by Aedes mosquitoes. It’s a flavivirus related to yellow fever, West Nile, Chikungunya, and dengue. The latest two that hit the U.S., Chikungunya and dengue, are painful and bad enough—and dengue can kill people […]

The virus you likely never heard of is steadily marching north from Brazil. It’s Zika, spread by Aedes mosquitoes. It’s a flavivirus related to yellow fever, West Nile, Chikungunya, and dengue. The latest two that hit the U.S., Chikungunya and dengue, are painful and bad enough—and dengue can kill people who are infected more than once. Zika adds an added nasty punch of perhaps causing microcephaly, a birth defect where babies are born with abnormally small skulls and brains, and often have developmental abnormalities.

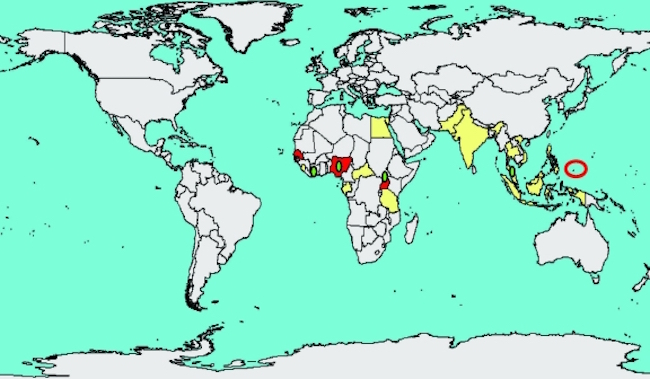

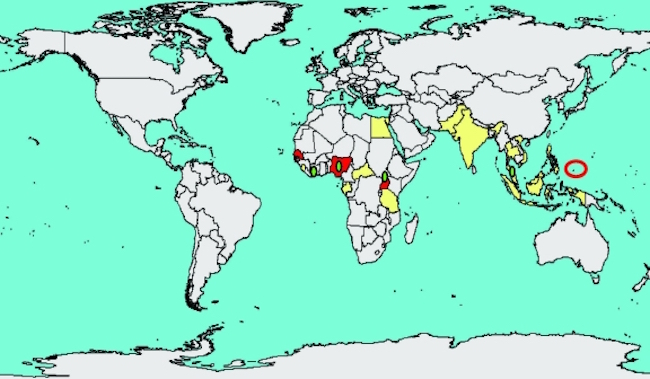

Zika was first found in mosquitoes in the Zika forest in Uganda, then isolated in people in Nigeria in 1968, though there was serologic (antibody) evidence of it’s being present through many African countries, India and Malaysia. It was first found outside these endemic areas in 2007, when there was an outbreak on Yap, a South Pacific island.

This first map, shows the “known distribution of Zika virus, 1947–2007“. The red circle represents Yap Island. Yellow indicates human serologic evidence; red indicates virus isolated from humans; green represents mosquito isolates.”

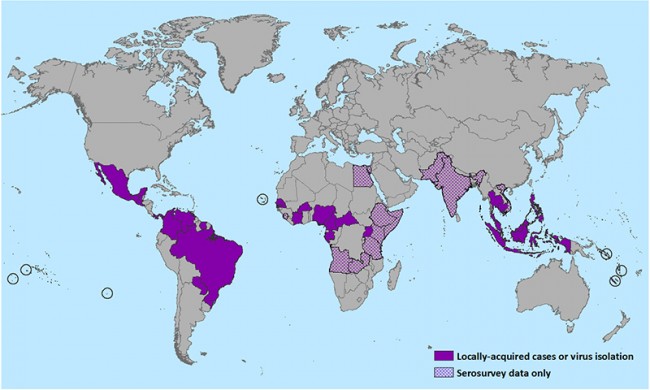

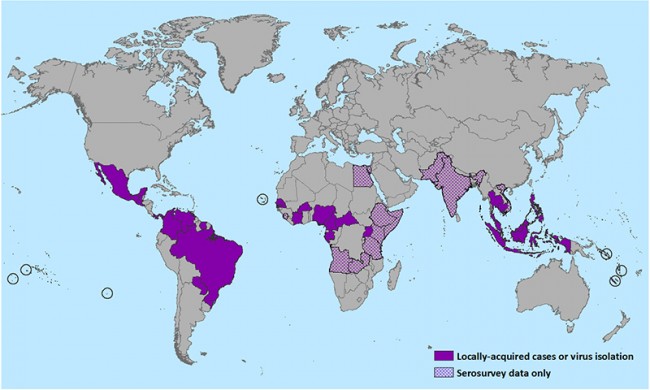

These maps are intriguing, showing how quickly Zika is spreading. A similar pattern was seen with Chikungunya, which only reached Europe in 2007, and the Americas in 2013. That same year, in the largest outbreak to date, 28,000 people in French Polynesia (11% of the population) became ill.

Recommended by ForbesColombia is also seeing a huge rise in Zika cases, now with more than a thousand new cases a week. Brazil saw its first infection in May 2015. Since then, there has been an explosive increase in cases (estimated at 440,000-1.3 million) and associated cases of microcephaly, now numbering more than 1,000. (Curiously, the CDC says this is about a 10-fold increase; the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) says it is a 20-fold increase.)

A map from December 2015 shows how Zika has spread northward since May, now with locally acquired cases in 10 Latin American countries, and travel-related cases diagnosed in the U.S. In just the time since I wrote the first draft of this post last week, Zika has spread further, most recently being found in Puerto Rico.

Given that mosquitoes don’t respect borders and that we now have Aedes-transmitted dengue and Chikungunya in the southern U.S., with similar climates as in now-endemic areas, I would expect us to soon begin seeing cases in Florida, Texas and the rest of the Gulf Coast, as well as perhaps California, as those areas all have the Aedes mosquitoes that transmit the virus.

How is Zika spread?

Those pesky mosquitoes are the main way people contract Zika, dengue and Chikungunya. A transfusion-associated case of Zika was reported from Brazil last week.

There are also now two reports of possible sexual transmission of Zika. The first report is quite intriguing. A malaria researcher returned to Colorado from a trip to collect mosquitoes in Senegal. Both he and his wife later became ill with Zika, though she did not join in his travel. He appears to have infected his wife, noting “patients 1 and 3 reported having vaginal sexual intercourse in the days after patient 1 returned home but before the onset of his clinical illness.” Though not proof of sexual transmission, it is likely, given the hematospermia (bloody semen) reported in these two cases.

Symptoms–Does Zika Cause Microcephaly?

Most of the infections are asymptomatic. Illness occurs 3-12 days after the bite from an infected mosquito and lasts 4-7 days. The symptoms of Zika are easily confused with dengue and Chikungunya—fever, rash, joint pain, headache. Conjunctivitis is apparently more common with Zika. Other than serious birth defects, prompting travel alerts, or the spike in Guillain-Barre paralysis seen in Polynesia, Zika seems to be generally milder that these other viruses…but that will likely change as we learn more. We thought the same when West Nile virus, a member of the same family, emerged.

The biggest concern about Zika thus far is whether this virus is the cause of the surge in cases of microcephaly. To me, this seems likely, given the increase of these birth defects noted both in Fiji and in Brazil, corresponding with the outbreaks of Zika. There is no definitive proof yet…but it is further evidence that there are now two cases of Zika virus being isolated from amniotic fluid, explaining how fetuses might become infected. There was another report from Brazil of Zika virus found in the blood and tissue of a newborn with microcephaly, who died within minutes of birth.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis is by reference lab work, so useful for hindsight, but not clinically. There are no rapid tests available in practice. But it’s useful to know what caused an infection, even if it is not treatable, as it might have implications for future care. For example, repeat dengue infections are much more likely to be life-threatening from hemorrhagic fevers than the initial illness.

There is only symptomatic treatment for any of these viruses—rest, fluids and pain meds, with acetaminophen (Tylenol) preferred. You should avoid aspirin or NSAIDs, at least until dengue is ruled out, as they could worsen the risk of bleeding.

Prevention

Avoiding mosquito bites is the mainstay of preventing any infection from the critters. With malaria, the vector Anopheles mosquito generally bites at night or dawn and dusk, so using bed nets is an important route of prevention.

These disease-spreading mosquitoes are spreading between countries by travel, climate change and occasionally by human transmission to the insects.

In the last few years, the U.S. has had an invasion of Aedes mosquitoes, A. aegypti and A. albopictus. The Asian tiger mosquito, A. albopictus, which transmits all of these viruses, is an aggressive daytime feeder, making it much harder to avoid. It also can adapt to colder temperatures, meaning we will have much more trouble with it wintering over. One of the scary things is that this mosquito species has become resistant to four of the six pesticides used against it. This is part of why I support the use of Oxitec’s genetically modified mosquitoes, which have shown a greater than 90% efficacy in reducing Aedes populations in South American trials.

One other thing that is important is protecting yourself from mosquito bites, even if you become ill with one of these viruses, so that you don’t infect other mosquitoes that feed on you, and thus fuel the spread of disease. Stay in, use a net or use an insect repellent—either permethrin on your clothes, or picaridin or DEET—on your skin.

It’s critical, too, to eliminate the breeding grounds for the mosquitoes, pools of standing water, as can occur in abandoned tires or buckets.

Travel

The CDC has issued a travel warning due to Zika for the countries in Latin America experiencing rapid spread, encouraging enhanced protection against mosquito bites. Pregnant women, in particular, are urged to take extra steps to avoid bites. The warnings should be applied more broadly, given the spread of Chikungunya and dengue as well, to other countries in Latin America.

Conclusion

Zika virus is the latest emerging infectious disease to grace the Americas. With globalization and climate change, we can expect to see more and more similar infections. The arboviruses dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika are likely to be growing problems in the U.S. over the coming year or two. Who knows—if global warming continues unabated, we might even see a resurgence of yellow fever in the south. Brace yourself for an exciting new year.

Source: Zika: Coming To America Through Mosquitoes, Travel And Sex – Forbes