Balcony Scene (Or Unseen) Atop the World; Episode at Trade Center Assumes Mythic Qualities

Published: August 18, 2001

Called ‘‘The B-Thing” and produced by four Vienna-based artists known collectively as Gelatin, the book is demure to the point of being oblique. What little explanation it contains appears to have been scribbled in ballpoint. Among the photos and schematic drawings, there are doodles of tarantulas with human heads.

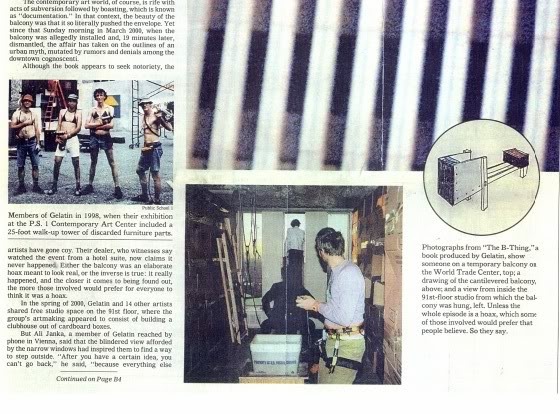

In short, the book belies the extravagance of the feat it seems to document: the covert installation, and brief use, of a balcony on the 91st floor of the World Trade Center, 1,100 feet above the earth. Eight photographs — some grainy, all taken from a great distance — depict one tower’s vast eastern facade, marred by a tiny molelike growth: a lone figure dressed in a white jacket, standing in a lectern-size box.

The contemporary art world, of course, is rife with acts of subversion followed by boasting, which is known as ”documentation.” In that context, the beauty of the balcony was that it so literally pushed the envelope. Yet since that Sunday morning in March 2000, when the balcony was allegedly installed and, 19 minutes later, dismantled, the affair has taken on the outlines of an urban myth, mutated by rumors and denials among the downtown cognoscenti.

Although the book appears to seek notoriety, the artists have gone coy. Their dealer, who witnesses say watched the event from a hotel suite, now claims it never happened. Either the balcony was an elaborate hoax meant to look real, or the inverse is true: it really happened, and the closer it comes to being found out, the more those involved would prefer for everyone to think it was a hoax.

In the spring of 2000, Gelatin and 14 other artists shared free studio space on the 91st floor, where the group’s artmaking appeared to consist of building a clubhouse out of cardboard boxes.

But Ali Janka, a member of Gelatin reached by phone in Vienna, said that the blindered view afforded by the narrow windows had inspired them to find a way to step outside. ‘‘After you have a certain idea, you can’t go back,” he said, ”because everything else seems very weak compared to it.”

Mr. Janka was happy to talk about the project, at least at first. After weeks of planning, he said, one night Gelatin — he, Florian Reither, Tobias Urban and Wolfgang Gantner — waited in the studio until dawn. At the appointed moment, the four, wearing harnesses, unscrewed the aluminum moldings that hold the window in place and used two large suction cups to remove the glass (air pressure adds about 300 pounds to the effort). As warm air streamed past, they outfitted the window with a cantilevered box, big enough for only one person at a time.

”The amazing thing that happens when you take out a window,” Mr. Janka said, ”is that the whole city comes into the building.”

Other artists in the studio have heard rumors of the balcony, but most are dubious. ‘I can tell you that it never happened,’‘ said Geoffrey Detrani, whose space was next to Gelatin’s. ‘‘To remove a window would be a pretty serious structural breach.”

But Gelatin, fearing expulsion from the country, had gone to great lengths to conceal their plot. The clubhouse afforded privacy and storage. By prior agreement, the group confiscated all film and video of the project taken by invited witnesses.

Still, how did a balcony escape the notice of one of the most security-conscious office towers in the world? An examination of the security system revealed that it was focused on the ground floor and basement, Mr. Janka said, adding, ‘‘There’s no surveillance on the facade itself.”

That is true, said Cherrie Nanninga, the director of real estate for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which until recently ran the World Trade Center. Port Authority officials, shown a copy of ”The B-Thing” by a reporter, reacted with disbelief, then outrage. Although their own investigation turned up no evidence, Ms. Nanninga said, ‘‘we have no reason to believe it didn’t happen.”

Window removal is considered so dangerous that when it is done the streets below are cordoned off, she said. ”It was really a stupid and irrational act that in my view borders on the criminal,” she said, adding that the stunt had jeopardized the studio program, whose space is donated by the Trade Center.

Removing the window may have been dangerous, but according to Walter Friedman, the owner of Dependable Glass, which performs that service for the World Trade Center, it is not that difficult. All it takes is four guys, some readily available equipment — and nerve, Mr. Friedman said.

Nerve is not something Gelatin lacks. They specialize in projects that require participants to sign a waiver.

In a piece called ”The Human Elevator,” strong men on scaffolding hoisted people to the roof of a three-story building in Los Angeles. And patrons in Munich were greased with baby oil and invited to slide naked down an esophaguslike chute formed by the bellies of a crew of overweight Germans.

Although Gelatin, which is representing Vienna in the Venice Biennale, has not shrunk from physical risk, they seem to think that merely discussing the balcony with a reporter was dangerous, perhaps because they are currently seeking permission to live on a vacant lot on Canal Street, as part of a forthcoming exhibition.

‘‘If you write about the balcony, maybe you can just not write about it too much,” Mr. Janka called back to say after the initial interview, the first of several calls protesting the appearance of an article, despite the fact that the artists had published the book.

To others involved in the project, it seemed reasonable that the appearance of ”The B-Thing” meant secrecy was no longer necessary. Josh Harris, the Internet entrepreneur once known for holding extravagant art parties, explained that Leo Koenig, the 24-year-old art dealer who represents Gelatin, got him involved.

The night before the B-Thing, Mr. Harris said, he rented a top-floor suite at the Millennium Hilton, across the street from the Gelatin studio, and invited people to what guests described as a night of decadence. Near dawn, he and several others took cameras and boarded a helicopter, communicating with Gelatin via cell phone.

‘‘We had to fly twice around the building before we could see them,’‘ said Mr. Harris, who is thanked in the book.

Afterward, Gelatin appeared at the hotel, where their success was toasted at a euphoric breakfast, according to five other witnesses, including Tanya Corrin, a video producer and writer, and David Leslie, a performance artist. ‘‘We just applauded the gutsy originality of it,” Ms. Corrin said. ”I think we all left feeling, wow, we just did something amazing, and nobody knows.”

Mr. Koenig now says the balcony never happened and, at any rate, he didn’t see it. The book, which costs $35 and was printed in a run of 1,200 copies, is meant to provoke questions about its veracity, he said.

At the suggestion that the project might have been faked, Mr. Harris seemed almost offended. He produced March 2000 credit card bills bearing charges of $2,167.44 from the Millennium Hilton and $1,625 from Helicopter Flight Service.

At about the same time that Mr. Harris was digging up proof, Gelatin was removing almost every trace of it from their Web site.

Moukhtar Kocache, the director of the studio program, insisted that the photos of the balcony were obviously faked. But digital manipulation experts disagreed. George Dash, the co-owner of Nucleus Imaging on East 30th Street, and a colleague, John Grasso, used magnifying loupes to examine a copy of ”The B-Thing.” Neither could detect inconsistencies. ”The angles are all too perfect,” Mr. Grasso said. ”It looks real to me. Absolutely. I’ve been doing this for 22 years.”

The balcony may be an art prank in the lineage of Yves Klein, who in 1960 disseminated a picture of himself leaping blithely out a window, an image revealed years later to be the product of deftly spliced negatives. But in its audacity, it seems more akin to tricksters who tested the limits of the World Trade Center in the 1970’s, including Philippe Petit, who walked a high wire strung between the towers.

‘‘This building needs things like that to happen, because otherwise it would die inside,” said Mr. Janka, who was under the impression that Mr. Petit had been deported for his action.

Although the Port Authority has not yet decided what, if any, action it will take against Gelatin, Mr. Janka might be relieved to learn that Mr. Petit, who still lives in New York, was simply required to give the city a free performance. He obliged by walking a tightrope to the top of the Belvedere Castle.

Photos: Members of Gelatin in 1998, when their exhibition at the P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center included a 25-foot walk-up tower of discarded furniture parts. (P.S. 1); Photographs from ”The B-Thing,” a book produced by Gelatin, show someone on a temporary balcony on the World Trade Center, top; a drawing of the cantilevered balcony, above; and a view from inside the 91st-floor studio from which the balcony was hung, left. Unless the whole episode is a hoax, which some of those involved would prefer that people believe. So they say.

Source: News Spike: 9/11: Jumpers Inc.