Powered by radios in trees, homegrown network serves 50 houses on Orcas Island

When you live somewhere with slow and unreliable Internet access, it usually seems like there’s nothing to do but complain. And that’s exactly what residents of Orcas Island, one of the San Juan Islands in Washington state, were doing in late 2013. Faced with CenturyLink service that was slow and outage-prone, residents gathered at a community potluck and lamented their current connectivity.

“Everyone was asking, ‘what can we do?’” resident Chris Brems recalls. “Then [Chris] Sutton stands up and says, ‘Well, we can do it ourselves.’”

Doe Bay is a rural environment. It’s a place where people judge others by “what you can do,” according to Brems. The area’s residents, many farmers or ranchers, are largely accustomed to doing things for themselves. Sutton’s idea struck a chord. “A bunch of us finally just got fed up with waiting for CenturyLink or anybody else to come to our rescue,” Sutton told Ars.

Around that time, CenturyLink service went out for 10 days, a problem caused by a severed underwater fiber cable. Outages lasting a day or two were also common, Sutton said.

Faced with a local ISP that couldn’t provide modern broadband, Orcas Island residents designed their own network and built it themselves. The nonprofit Doe Bay Internet Users Association (DBIUA), founded by Sutton, Brems, and a few friends, now provide Internet service to a portion of the island. It’s a wireless network with radios installed on trees and houses in the Doe Bay portion of Orcas Island. Those radios get signals from radios on top of a water tower, which in turn receive a signal from a microwave tower across the water in Mount Vernon, Washington.

“I think people were leery whether we could be able to actually do it, seeing as nobody else could get better Internet out here,” Sutton said.

But the founders believed in the project, and the network went live in September 2014. DBIUA has grown gradually, now serving about 50 homes.

“It wasn’t that hard”Erin Bennett

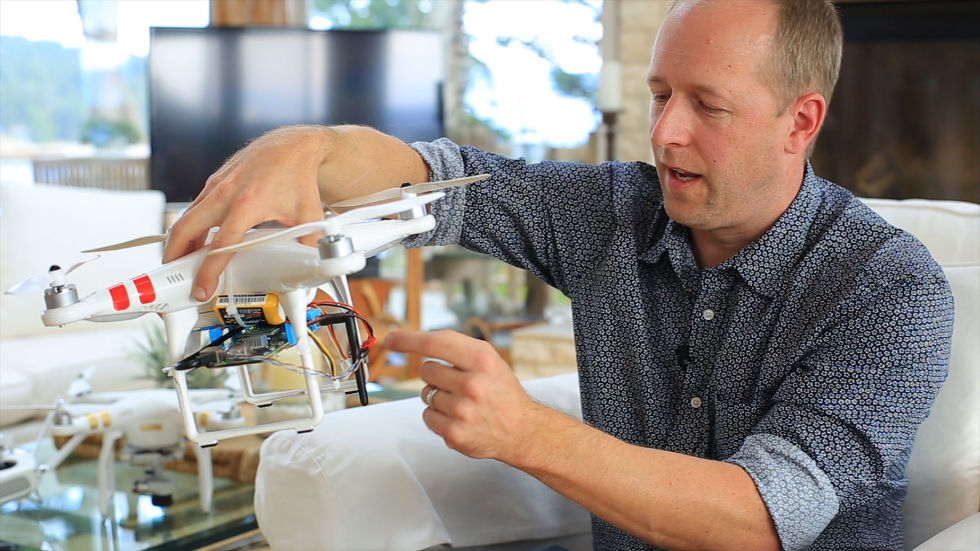

Sutton holds a drone he used to analyze potential radio locations.

Back in 2013, CenturyLink service was supposed to provide up to 1.5Mbps downloads speeds, but in reality we “had 700kbps sometimes, and nothing at others,” Brems told Ars. When everyone came home in the evening, “you would get 100kbps down and almost nothing up, and the whole thing would just collapse. It’s totally oversubscribed,” Sutton said.

That 10-day outage in November 2013 wasn’t a fluke. At various times, CenturyLink service would go out for a couple of days until the company sent someone out to fix it, Sutton said. But since equipping the island with DBIUA’s wireless Internet, outages have been less frequent and “there are times we’re doing 30Mbps down and 40Mbps up,” Brems said. “It’s never been below 20 or 25 unless we had a problem.”

Unlike many satellite and cellular networks, there is no monthly data cap for DBIUA users.

Sutton, a software developer who has experience in server and network management, says he’s amazed how rare projects like DBIUA are, claiming “it wasn’t that hard.” But from what he and Brems told Ars, it seems like it took a lot of work and creative thinking to get DBIUA off the ground.

“The part of Orcas Island we’re on looks back toward the mainland,” Sutton said. “We can see these towers that are 10 miles away, and you realize, ‘hey, can’t we just get our own microwave link up here to us from down there, and then do this little hop from house to house to house via wireless stuff?’”

One of StarTouch’s microwave backhaul towers.The DBIUA paid StarTouch Broadband Services about $11,000 to supply a microwave link from a tower on the mainland to a radio on top of Doe Bay’s water tower. The water tank, at about 50 feet, is the only structure that’s high enough to create a point-to-point link to the mainland. It is owned by the Doe Bay Water Users Association, which let DBIUA install the radios and other equipment.

Sutton and friends set up Ubiquiti radios throughout the area, on trees and on top of people’s houses, to get people online. Sutton used Google Earth to map out the paths over which wireless signals would travel, and then the team conducted on-the-ground surveys to determine whether one point could reach another.

Flight of the dronesThe rural Orcas Island has a lot of hills and obstacles that could disrupt the wireless signals, and it would have been “prohibitively expensive” for DBIUA to install its own towers. As such, many of the radios had to be installed in trees. Sutton had a solution for this as well—DBIUA would use a drone to determine whether a radio on a treetop could reach other points of the network.

Initially, the drone was equipped with a camera to determine whether the treetop could “see” the next radio in the network. Later, Sutton added radios to the drone itself so he could test the wireless signal at the treetop. When they confirmed a tree would work, “we hired the person to climb up the tree and install the radios,” Sutton said.

Most homes in the network have a radio on the roof or the side of the house that points to one of about 10 relay points, which have multiple radios for receiving and distributing signals. Relay points themselves can be on a tree, a pole, or on the side of a house.

“For some people, like me, the signal comes to my tree, and then down into my house to service me,” Sutton said.

A relay point has one radio to receive a signal and a couple more radios to send it in different directions. Each relay point is similar to the setup on top of the water tank.

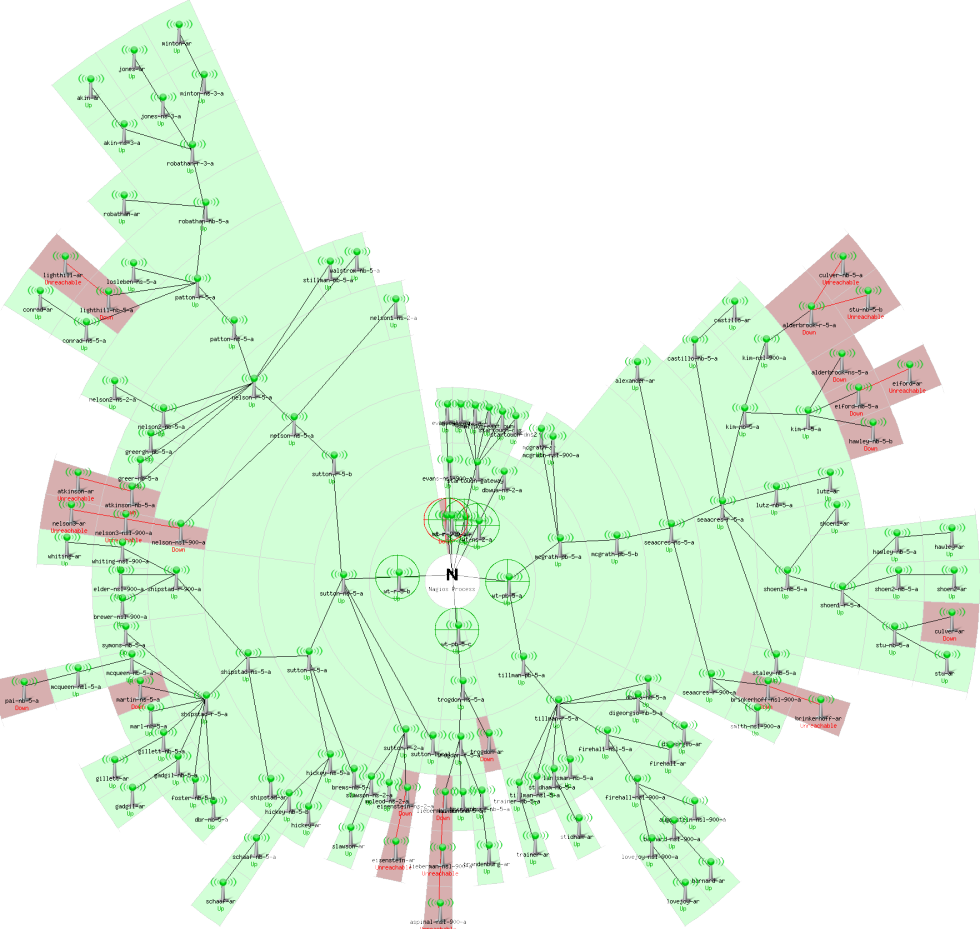

DBIUA

Network status map.

A tree will generally have a box with DBIUA equipment, and Power over Ethernet (POE) cables going up the tree to the radios. POE cable also goes from the box “back to the closest power source, usually in someone’s home, and we can then provide that home a connection to the network,” Sutton explained. “In the person’s home is the power brick that puts power into the Ethernet cable,” providing electricity to the outdoor equipment. The system uses low-voltage power, with each radio requiring about eight watts.

The network uses 5.8GHz and 900MHz frequencies, and a little bit of 3.65GHz, mostly avoiding the crowded 2.4GHz band. All the connections need line-of-sight, “especially for 5.8GHz,” since the higher frequencies are more easily blocked, Sutton said.

There are now about 200 radios spread throughout the coverage area, and each homeowner who pays for service has a Wi-Fi router in the home to access the Internet.

Listing image by Chris Sutton

It can be doneThough DBIUA’s Internet service is a rarity, there are similar projects elsewhere. Brooklyn Fiber in New York was founded by two brothers to sell Internet access to the community. A volunteer project called the Red Hook Initiative buys Internet service from Brooklyn Fiber in order to provide free Wi-Fi.

In Germany, residents of a small town called Löwenstedt built their own Internet service. One Ars reader who lives in Norway personally installed fiber lines to his own property.

Further Reading

Want fiber Internet? That’ll be $383,500, ISP tells farm ownerGood news, though: Small ISP promises to do the same work for just $42,000.

“There’s actually a thriving global network of community wireless initiatives—many of whom stay in regular touch and swap information on recent software advances, promising hardware, and innovative business models,” Sascha Meinrath, X-Lab founder and Penn State telecommunications professor, told Ars. There are such projects in Austria, Spain, and Greece, and another that serves tribal reservations outside San Diego, he noted.

Just like on Orcas Island, these projects came into being because residents were frustrated with Internet access options from private companies.

Private ISPs have demanded as much as $383,500 from residents who want service and live in sparsely populated areas. Some cities and towns have built their own Internet services, but laws in numerous states make that difficult. A law in Washington state “authorizes some municipalities to provide communications services but prohibits public utility districts from providing communications services directly to customers,” according to attorney James Baller of the Baller Herbst Law Group, who has been fighting attempts to restrict municipal broadband projects for years.

While CenturyLink is the main ISP on Orcas Island, a company owned by Orcas Power & Light Co-op (OPALCO) is building out a fiber network in the San Juan County islands. That company says construction will cost “$1,500 to $6,000 on average” for each home, and residents would be responsible for anything beyond the first $1,500.

DBIUA charges much less, but even its low prices “can be significant depending on your income,” Brems said. The DBIUA customers include “lots of retired people and people living off the land. We had to convince people we knew what we were doing,” he said.

StarTouch installing a microwave link at the water tower.

DBIUADBIUA spent about $25,000 in total to build the network, and an anonymous resident provided the money in a 3-year, interest-free loan. Residents paid $150 to become members of the DBIUA and $75 a month for Internet service, which goes toward paying down the loan. The monthly fees also cover the $900 a month DBIUA pays StarTouch for bandwidth.

Further Reading

One big reason we lack Internet competition: Starting an ISP is really hardCreating an ISP? You’ll need millions of dollars, patience, and lots of lawyers.

DBIUA needed 25 customers to pay the bills and stay afloat. At 50 now, the organization is paying the loan off a bit more quickly. Sutton hopes to lower the monthly price residents pay after the loan is paid off.

“We’re not making any money here, we’re just covering our costs,” Sutton said. Besides residents, DBIUA also provides Internet access to the water plant and the Doe Bay Resort. The water plant uses very little bandwidth, and the resort also has a fiber connection to OPALCO, he said. (DBIUA talked to OPALCO about purchasing fiber backhaul, but was unable to get wholesale rates, making it more economical to go with StarTouch, Sutton said.)

To prevent Internet slowdown, DBIUA builds slowlyDBIUA isn’t adding customers as fast as it can. Customers who signed up from the beginning got first priority.

“You had people who committed up front to say, ‘we’re going to help you jump start this,’” Sutton said. “The system is up and it’s really great and it’s fast and then you get a whole bunch of people who come in later and say, ‘oh, I wanted to wait and see if this is going to work and now I want on.’”

Sutton and friends don’t want to oversell the network and go down the same path as CenturyLink, which wasn’t able to provide even the meager 1.5Mbps download speeds it promised. They decided to take their time to add capacity before connecting everyone who wants service, but they expect to get up to 60 homes served by the end of the year.

The network port on the mainland that DBIUA connects to provides 100Mbps. Tests at the water tank show that the DBIUA network has real-world bandwidth of about 70Mbps down and up across the whole system.

There are no specific speed limits for each home, but the system automatically manages the load to prevent one person from hogging all the bandwidth.

“We monitor all the connections and if someone is using a lot of bandwidth for a long period of time, we talk to them and figure out what they are doing,” Sutton said. “Often times it’s people watching Netflix and then falling asleep and then it keep auto-playing things all night long.”

In practice, customers get the speed they need—at peak usage times, total bandwidth usage across the entire network is 30Mbps or so, well within the 70Mbps available.

“It’s really those teenagers that consume all the bandwidth,” Sutton said, describing his two kids “in the living room, and both of them are on their screens watching YouTube with a big smile on their face.”

The microwave connection to the mainland is strong enough to handle more subscribers, but adding homes to the network requires bolstering capacity in specific areas, Sutton explained.

No “waiting around for corporate America”

Capacity can be boosted by adding radios—or with some tree trimming. If there’s “a location where there was a tree in the way,” Sutton said, they’d “trim the tree so now we have better throughput there to manage more people.” The StarTouch link uses burstable billing, with prices going up the more they use.

CenturyLink’s promises “never came to fruition”Sutton grew up on Orcas Island before living in Seattle for a while. He moved back to Orcas about eight years ago, telecommuting to his job in Seattle. “When the Internet connection was crappy I couldn’t do my job,” he said. “So this is personal.”

CenturyLink promised better speeds over the years “but that never came to fruition,” Sutton said. “Just waiting around for corporate America to come save us, we realized no one is going to come out here and make the kind of investment that’s needed for 200 people max.”

When contacted by Ars, CenturyLink said it upgraded its fiber backbone on Orcas Island in May and provides “up to 20Mbps” speeds “depending on where you reside in the island.”

But in the Doe Bay area, CenturyLink confirmed to Ars that it offers speeds only up to 1.5Mbps. The company also confirmed to Ars that “we are not currently adding broadband customers in Doe Bay.”

Doe Bay residents still buy home phone service from CenturyLink since DBIUA provides only Internet access. And a few DBIUA customers have even kept their CenturyLink DSL Internet as a backup in case DBIUA goes down.

But overall, CenturyLink’s poor infrastructure in Doe Bay is reminiscent of AT&T, which has refused to hook up homes in certain DSL areas where it hasn’t invested sufficiently in network. CenturyLink has gone so far as to tell customers who cancel their DSL service that they will not be able to start it up again, Brems said. “CenturyLink said, ‘we’ll take it off, but you’re never going to get back on.’”

The rest of the teamBrems, who works in advertising and marketing and is now mostly retired, lived in Seattle for more than 20 years before moving to Orcas Island about 15 years ago. He has been struck by the “can-do” spirit of the community, which in the past built its own water plant and fire station, he said.

“They didn’t wait for someone else to come along and say, ‘I can come and save you guys if you want,’” he said.

Further Reading

500Mbps broadband for $55 a month offered by wireless ISPYou’ve probably never heard of Webpass—and you probably won’t get its service.

While Sutton spearheaded the DBIUA project, others provided important expertise. Brems, for example, used his marketing knowledge to help convince people that the project could work and get the word out by writing press releases.

The other founders are Orcas Island airport manager Tony Simpson, who previously worked for the Air Force and Boeing; lawyer Shawn Alexander, who specializes in real estate, land use, and contracts; and Tom Tillman, co-owner of a sporting goods store and a former CenturyLink installer.

Alexander’s legal expertise helped in drafting contracts the members of DBIUA need to sign. The agreements require homeowners to keep hosting and supplying power to DBIUA equipment even if they stop buying the Internet service later on. (The power costs are only about $12 a year, Brems said.)

“We needed agreements in place that if you were to sell [the house], that the person who bought it knew there was a responsibility to keep the service going whether they chose to take advantage of it or not,” he said.

A smooth ride—most of the timeThe network has run perfectly for long stretches of time, requiring little more than basic maintenance. But there have been occasional glitches.

Enlarge / Chris Sutton.

Erin BennettEarly in the network’s life, Sutton got an alert at 2 am that a relay point was down. An in-person investigation determined that a sheep had disconnected an extension cord that was sitting in the middle of a field. Battery backup kept the radio running for about six hours; the 2 am alert arrived when the battery ran out.

To make sure the cord would be weather- and animal-proof, “we decided to just dig a trench through the field” to bury the line, Sutton said.

Another, more serious problem came just a few weeks ago. The radio installed by StarTouch on the mainland broke late on a Friday, and no one could fix it until the next week.

That meant there was no Internet service from DBIUA, but a backup plan was cobbled together. On Saturday, Sutton climbed the water tank and pointed a Ubiquiti radio at a different StarTouch tower on the mainland. The Ubiquiti radio only provided about 10Mbps, “which got us back going, but it was obviously limping along.”

On Monday, StarTouch replaced the radios at both ends, on the mainland and on top of the water tower. But Sutton was on a business trip and couldn’t get back to the water tower until Wednesday to switch the network over to the new connection.

During outages, customers can call a help line number to hear a message with the latest information on the network status. People on the island understand that this is all a volunteer effort and that there will be occasional problems.

“They really appreciated us just being up front with what was going on,” Sutton said.

The weekend outage was a learning experience, and now Sutton is considering leaving the backup radio on the water tower permanently in case the system needs to fail over to the second radio on the mainland. The router that DBIUA has at the water tower could then automatically switch to the second radio if the primary link goes down.

A true patriotThis past summer, Sutton was named the Doe Bay Community Association Patriot of the Year at the Fourth of July celebration. “In the past 18 months, he has literally driven every back road, climbed countless tall trees and run hundreds of sight lines…,” Brems said on his friend’s behalf. “He has unpacked, inventoried, programmed, and installed dozens of pieces of equipment. He has scaled the Doe Bay water tank multiple times.”

While Sutton has been the driving force of DBIUA, he is looking to impart some of his knowledge to other members of the association so they can fix problems when he can’t. Using Slack, they set up a training channel where Sutton is teaching them how the system works. He’s given members limited access to the monitoring system so they can get familiar with it, and he will eventually provide administrative rights so they can manage the network.

The group is also thinking up new ways to troubleshoot the network. One idea is to “put a Raspberry Pi at the different relay points to do speed tests [to the water tank] and log that over time,” Sutton said. That way, if people call and say Internet access is slow, DBIUA can check to see whether the problem is within its own network or in the connection to StarTouch.

Raspberry Pis could also monitor voltage on batteries to determine whether a radio has switched to backup power. That information could provide several hours of warning before a radio goes out completely.

While there’s room for growth and improvement, the current benefits have been obvious for service members. In mid-August, a few weeks before the DBIUA outage outlined above, there was a major outage affecting both wired and wireless broadband providers caused by a car crashing into a major utility pole on the island.

“I think so many other communities could do this themselves.”

Just about everyone was down for nearly an entire day—but not DBIUA.

The crash “took out a major fiber line,” Sutton said. “Almost all Internet in San Juan County (Orcas, Lopez, and San Juan Island) went out. AT&T, T-Mobile, [and] Sprint cell phone service went out. The only Internet that continued to work was the school, library, and the DBIUA, all of which were using StarTouch microwave for their backhaul. I did a little bit of gloating for sure.”

With all the success, people in other parts of Orcas have since asked Sutton to set up networks for them. “I’m like, ‘no, but I can tell you how to do it,’’’ he said. So although networks like DBIUA’s remain rare for now, Sutton believes it can be duplicated in more places than you’d expect.

“I think so many other communities could do this themselves,” he said. “There does require a little bit of technical expertise but it’s not something that people can’t learn. I think relying on corporate America to come save us all is just not going to happen, but if we all get together and share our resources, communities can do this themselves and be more resilient.”

.

Source: How a group of neighbors created their own Internet service | Ars Technica