This story was produced by the Lens, a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom serving New Orleans.

Ten years after Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent floods from the failed federal levees, out-of-town media and politicians are still getting some things wrong. Here are five of the most stubborn myths about the disaster, the recovery, and the city of New Orleans—plus one self-delusional bonus myth we just can’t let stand.

1. No one could have predicted it.

“That ‘perfect storm’ of a combination of catastrophes exceeded the foresight of the planners, and maybe anybody’s foresight.”

— Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, Sept. 5, 2005

“I don’t think anybody anticipated the breach of the levees.”

—President George W. Bush, Sept. 1, 2005

“Well, God bless everyone, because nature we can’t control. She does what she wants.”

—Rep. Marcy Kaptur, D-Ohio, April 30, 2015

There are two problems. The first is thinking of what happened as a natural disaster.

Hurricane Katrina itself was a natural phenomenon, but most of the flooding in and around New Orleans was the result of the poor construction and design of the city’s flood-protection system by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, causing more than 50 breaches. Researchers estimated that water pouring in through the broken levees may have caused as much as 84 percent of the flooding. The extent of the flooding also made it harder to push the water out of the city because many pump stations were flooded. Some that worked were useless because they were just recirculating water in and out of the breaches.

The other problem: A disaster of this scale had been predicted, and levee failure had been discussed.

A Katrina-like catastrophe was predicted as recently as one year before the storm. In 2004, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the state office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness conducted the “Hurricane Pam Exercise.” The exercise modeled a Category 3 hurricane hitting New Orleans, overtopping the levee system and flooding the city with up to 20 feet of water.

The Pam model showed levees being overtopped, but it did not predict that the levees would break.

That possibility, however, did appear in the Times-Picayune’s 2002 series, “Washing Away.” That series described a worst-case scenario storm, one even more intense than Katrina, hitting the metro area. Experts interviewed in the series described a scenario where the city’s levees, combined with its bowl-shaped geography, would trap storm surge water inside for weeks or months in the event of major overtopping or a breach.

“Hundreds of thousands would be left homeless, and it would take months to dry out the area and begin to make it livable. But there wouldn’t be much for residents to come home to. The local economy would be in ruins,” reporters Mark Schleifstein and John McQuaid wrote.

More troubling, though, were the unheeded warnings of possible levee failure one year before Katrina.

In 2004, residents who lived near the 17th Street Canal, which was breached in the storm, reported water pooling in their yards to the water utility, the New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board. This was a sign that the levees were likely leaking, an early signal of their instability. But the Corps of Engineers was never informed of the problem.

2. New Orleans is below sea level.

Photo by AFP/Getty Images

“An estimated 80 percent of the below-sea-level city was under water, up to 20 feet deep in places, with miles and miles of homes swamped.”

—Associated Press, Aug. 30, 2005

“It makes no sense to spend billions of dollars to rebuild a city that’s seven feet under sea level, House Speaker Dennis Hastert, R-Ill., said of federal assistance for hurricane-devastated New Orleans.”

—Associated Press, Sept. 1, 2005

“For instance, an existing high school geography standard requires students ‘explain how humans interact with their environment.’ Then, a series of bullet points outlines specific approaches for teachers to use in class, such as talking about how New Orleans is below sea level for a lesson in land usage.”

—Sioux Falls Argus Leader, Nov. 16, 2014

Like the unpredictable natural disaster myth, New Orleans’ low elevation has played a role in political debates about whether the city is a worthwhile investment. Some have even asked why the city was built in the first place.

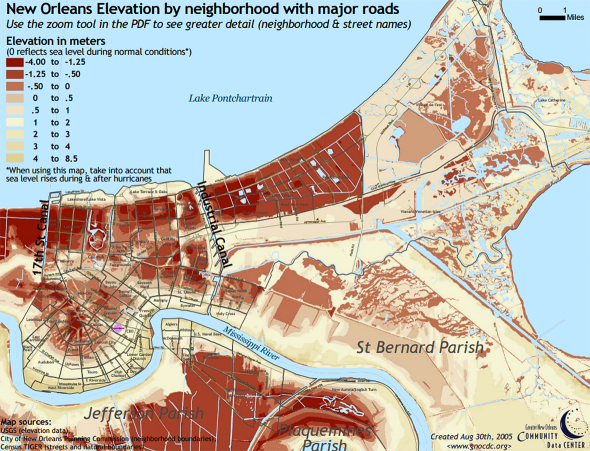

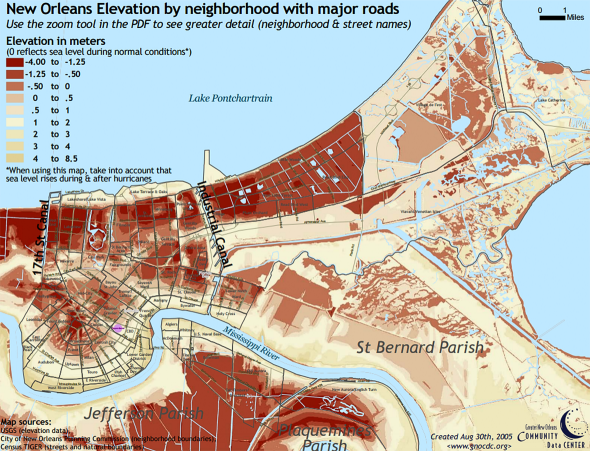

This one is half true: About half of New Orleans is below sea level. But even some areas above sea level, including much of the Lower 9th Ward, flooded after Katrina because of levee failures.

In a 2007 report, Tulane University geographer Richard Campanella found that 51 percent of the urbanized area in metropolitan New Orleans was above sea level. In 2000, 185,000 people in the city lived above sea level.

This map produced by the Data Center, a New Orleans think tank, makes it clear:

Courtesy of the Data Center

For much of the city’s first 200 years, most of its population lived on high ground. The oldest parts of the city, near the Mississippi River, can be more than 10 feet above sea level.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, a citywide drainage system and automobiles allowed New Orleanians to live farther away from the river, and developers began building in low-lying areas closer to Lake Pontchartrain.

But even much of that was once on higher ground than it is now. Ironically, the city’s flood control systems have caused it to sink. The first problem was the levee system, which, for the most part, keeps the area dry. Southeast Louisiana was built by sediment carried down the Mississippi River, deposited across the delta when the river overtopped its banks during spring floods. The levees prevented that annual replenishment.

The city’s drainage system—like the levees, built to keep the population dry—further contributed to the problem. The city was built on wet delta soil; the protected land inside the levees needs rainwater to remain hydrated. When too much water is pumped out, the soil dries and sinks—a process called subsidence—and the city ultimately becomes more vulnerable to catastrophic flooding.

3. Shooters were picking off cops and relief workers.

“Storm victims were raped and beaten, fights and fires broke out, corpses lay out in the open, and rescue helicopters and law enforcement officers were shot at as flooded-out New Orleans descended into anarchy today.”

—Associated Press, Sept. 1, 2005

“Our hotel was overrun with gangs.”

—Brian Williams, interview published July 26, 2014

This is perhaps the most outrageous example in the “post-Katrina crime wave” genre.

There was, of course, the purported chaos at the city’s two shelters of last resort: the Superdome and the convention center. The rape and murder of a 7-year-old girl at the convention center, dozens of killings at the Superdome, bodies piled up at both.

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

But by the end of September 2005, reporting by the Times-Picayune debunked many of these stories. In fact, officials only confirmed one killing at either site: Danny Brumfield, who was shot by police.

There were also the reports of mass looting, which led to an order authorizing police to shoot looters. Though there were many confirmed reports of looting after the storm, at least some of the alleged “looting” appears, in many cases, to have been desperate people gathering food, water, and supplies. Even early news stories included reports of people carrying food.

But the stories of citizens shooting at relief workers and police may trump those because of the consequences. Reports of officers being shot in New Orleans appear to have contributed to the decision by officials in a nearby suburb to seal off a bridge over the Mississippi River, leaving hundreds stranded on the flooded side of the river.

It also played a role in the infamous Danziger Bridge shootings, in which police officers opened fire on unarmed civilians crossing the bridge, killing two and seriously injuring four. Initial police reports claimed that people on the bridge were firing on several officers and a group of relief workers, but those were later proven false in court.

The media took much of the blame for the over-the-top coverage. But as former Times-Picayune reporter Gordon Russell, who now works for the New Orleans Advocate, noted, “their information was often coming from people who would ordinarily be considered reliable sources,” such as Mayor Ray Nagin and Police Superintendent Eddie Compass.

4. The Recovery School District was created due to Hurricane Katrina.

“One prototype is the all-charter, state-run Recovery School District in New Orleans, which was created in the wake of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation.”

—Los Angeles Times, Feb. 8, 2015

“According to a UIUC news release on the article, after Katrina, the state of Louisiana took over 102 of the Orleans Parish School Board’s 117 schools that were deemed worst performers, and created the Recovery School District (RSD).”

—WUIS-FM, June 1, 2015

Although it’s true Hurricane Katrina hastened the expansion of Louisiana’s state-run Recovery School District, the district was not born from the storm.

The Recovery School District was created in 2003. The name comes from its mission to help failing schools recover academically. It was a natural next step in the state’s accountability system established in mid-1990s. Going into the 2005–06 school year, the RSD already had taken over a handful of schools in New Orleans.

It was after the storm, in a special session of the legislature, that lawmakers changed the threshold for failing and allowed for the state takeover of a failing district. The move was clearly targeted at New Orleans’ crippled school system.

That change enabled the RSD to take over a majority of the city’s schools, leaving only the highest-performing ones under the Orleans Parish School Board’s control.

Today, the districts operate side by side. The RSD converted schools to charters and now oversees the country’s first all-charter district. The school board operates a majority-charter district but, contrary to some inaccurate rhetoric, the district still runs five traditional schools.

5. Everything is better now.

Photos by Mario Tama/Getty Images

“There are three ways things could have gone.

In the first story, New Orleans slides into its own wet grave, another urban tragedy of geography and economics. In the second story, New Orleans rebuilds itself as it was before — a sleepy southern belle of a town serving up wet weekends of intemperance. In the third story, Hurricane Katrina somehow kickstarts an age of innovation and an economic renaissance in a city written off for dead.

The Big Easy has chosen the third path — the hard path, and their struggle has revealed both the tantalizing allure, and the deep challenges, of reinventing a city.”

—The Atlantic, April 8, 2013

“Hurricane Katrina gave a great American city a rebirth.”

—Chicago Tribune, Aug. 13, 2015

The myth of the Katrina “reset” is popular with national media. The idea is that the storm and the floods that followed left the city a blank slate, allowing its leaders to rebuild it better than it was before: better planning, more efficient government, and no corruption.

The most recent, and possibly the most offensive, example was a column by Chicago Tribune writer Kristen McQueary. As a member of the newspaper’s editorial board, McQueary recently spoke to New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, who was making the rounds in the runup to the anniversary.

“I find myself wishing for a storm in Chicago — an unpredictable, haughty, devastating swirl of fury. A dramatic levee break. Geysers bursting through manhole covers. A sleeping city, forced onto the rooftops,” McQueary wrote. “That’s what it took to hit the reset button in New Orleans. Chaos. Tragedy. Heartbreak.”

The truth is more complicated than that.

It’s true that the city has grown from near-abandonment immediately after the storm to 80 percent of its pre-Katrina population, and it continues to grow faster than most other major cities. Its police department and jail are undergoing massive reform efforts. And tax collections are up year over year. The city’s schools are showing large gains in student test scores and graduation rates, according to a recently released study.

Still, the floods were devastating, and they continue to affect the area. About 1,800 people died, many of those in New Orleans. Nearly 80 percent of New Orleanians’ homes were flooded.

Ten years later, the city still suffers many blighted homes and overgrown lots. Violent crime continues to be a problem, and the city’s homicide rate consistently ranks near or at the top nationwide. The city’s fiscal progress could be undone by millions of dollars in unmet obligations. And advances from the police department and jail reforms are fitful.

The sweeping school overhaul also remains extremely controversial. Thousands of public school teachers lost their jobs after the storm and the state takeover. Schools in the Recovery School District still rank low, with about 40 percent earning a “D,” “F,” or “T” (ungraded turnaround school) in the state’s letter-grade accountability system. And a poll released Monday found that only 34 percent of black New Orleanians, whose children make up most of the city’s public school enrollment, think schools have improved, compared with 55 percent of whites.

Many people were never able to return. The overall population is lower, and the city has 100,000 fewer black residents now than before the storm, though it is still majority black. The city’s black population has not seen the same income gains as its white population. A report by the Data Center found that while the percentage of white middle- and upper-income households increased after Katrina, the percentage of black households in the same income tiers has shrunk.

Although the area has seen job growth, much of it has been in low-wage tourism and retail jobs. The city’s overall poverty rate is 27 percent, compared with 16 percent nationally. The New Orleans rate is virtually the same as it was before the storm. The childhood poverty rate is 39 percent, 17 percentage points above the national average and only a slight decrease from 41 percent in 1999.

Meanwhile, the city’s lack of affordable housing is reaching a near-crisis point. About 50 percent of the city’s residents spend more than 35 percent of their income on housing, and 37 percent spend more than half their income on housing.

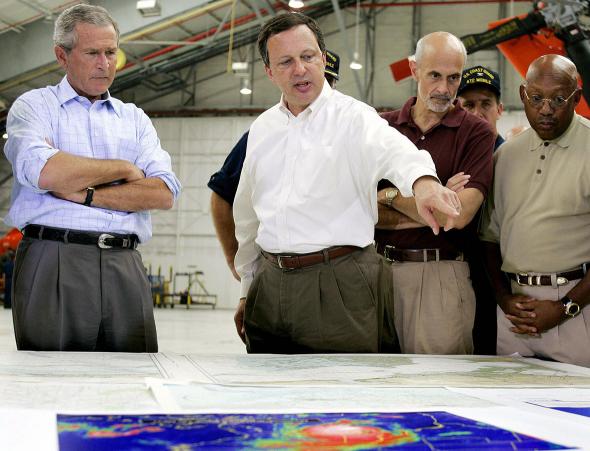

6. Then–FEMA chief Michael Brown did a great job.

“Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job.”

—President George W. Bush, Bush Press Archives, Sept. 2, 2005

Photo by Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images

OK, fine: It’s actually not a widely held myth that Michael “Brownie” Brown, who was the Bush administration’s FEMA director when Katrina hit, handled the disaster competently. Bush didn’t even seem to believe that for very long. Shortly after Bush’s public praise, Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff removed Brown from the Gulf Coast.

Ten years later, the only person who believes Brown did anything close to a heckuva job may be Brown himself. On Thursday, two days before the anniversary, Politico published a piece by Brown titled “Stop Blaming Me for Hurricane Katrina.” In it, Brown disabuses readers of the notion that he was to blame for the city’s incomplete evacuation, cites a breakdown in the proper “chain of command” under Chertoff, and complains about his relationship with the press.

Of those, the first is the only one really worth addressing. To get a good idea of how Brown was behaving while New Orleans was devastated, it’s best to check source documents, such as emails between Brown and his staff in the days immediately before and after the storm. Luckily, those are easy to find.

Emails showed that Brown dismissed reports that the city’s levees had breached and seemed to be preoccupied with his appearance as he anticipated national television interviews. His exchanges with Marty Bahamonde are also telling. Bahamonde, a FEMA public affairs official, was notably the only FEMA employee in the city of New Orleans in the days before the storm. Brown later testified before a congressional committee that the agency had more than a dozen officials in the Superdome.

On Aug. 31, 2005, Bahamonde sent a desperate email to Brown telling him that the Superdome was quickly running out of supplies and that medical patients were in imminent danger of death.

“We are running out of food and water at the dome,” Bahamonde wrote.

“Thanks for the update. Anything specific I need to do or tweak?” Brown responded.

Brown would later testify that Bahamonde said the Superdome had “plenty of food.”

The same day Bahamonde sent the email about the dire conditions in the Superdome, Brown’s press secretary let FEMA employee Cindy Taylor know that “It is very important that time is allowed for Mr. Brown to eat dinner” and would need plenty of time to “get to and from a location of his choice, followed by wait service from the restaurant staff, eating, etc.”

Taylor forwarded the email to Bahamonde.

“Just tell her that I just ate an MRE and crapped in the hallway of the Superdome with 30,000 other close friends,” Bahamonde wrote back.

Source: Hurricane Katrina, 10 years later: The myths that persist, debunked.